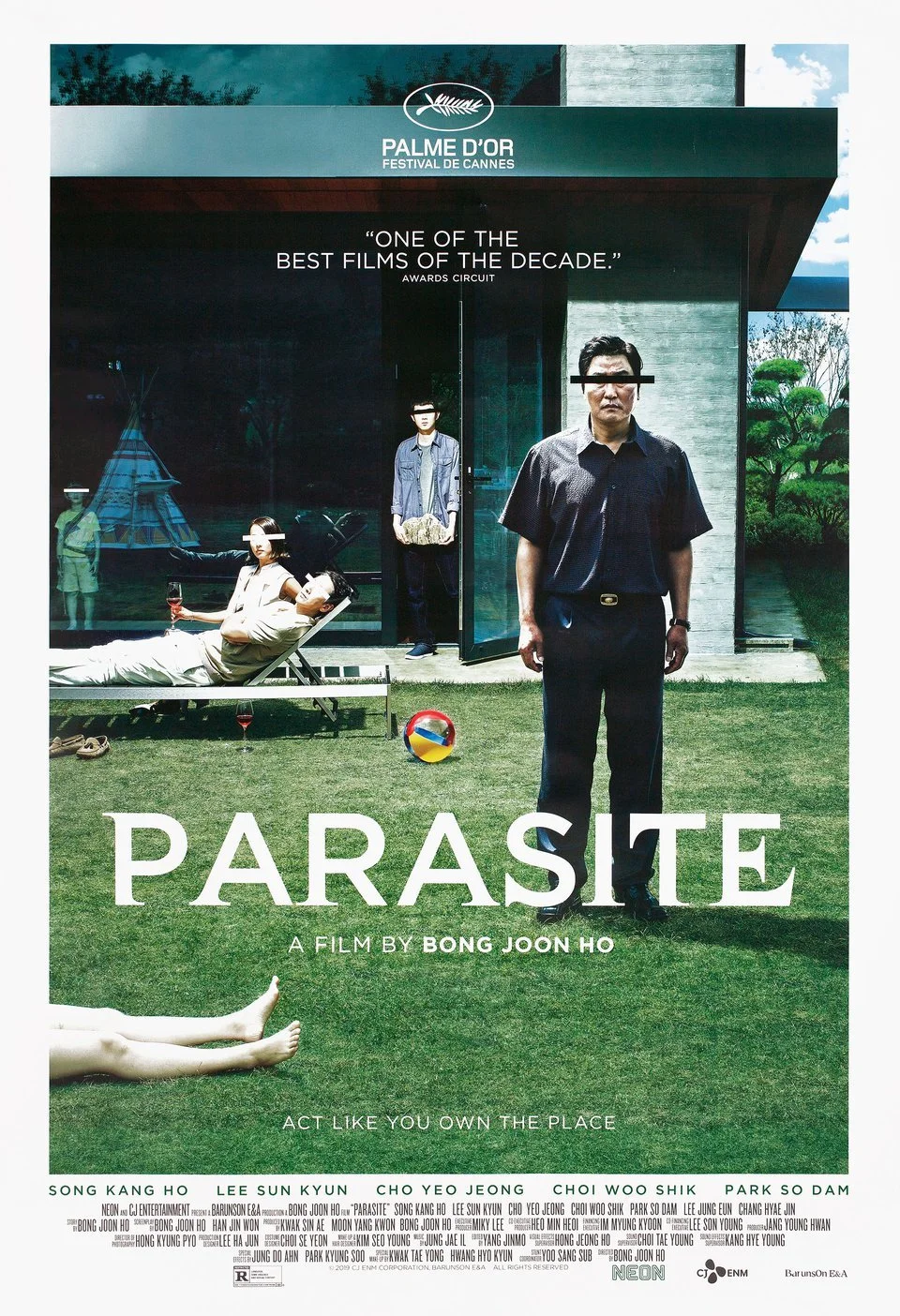

Parasite Movie: A Study of Class, Fate, and the Illusion of Control

Editor’s Note: Parasite isn't just a thriller; it's a mirror. In today's guest feature, aspiring director Praveen Kumar moves beyond the plot to dissect the film's architecture, its commentary on class, and the terrifying realization that—rich or poor—none of us are truly in control. SPOILER ALERT: YES, this article contains major spoilers for the ending of Parasite. If you haven't seen it, you’ve been warned.

Hey, this is me, Praveen Kumar.

Let’s take a long pause and breathe before stepping into this world. Because watching Parasite is not just watching a film. It feels like sitting quietly after something has shaken you from the inside. It stays. It lingers. It questions you.

After watching Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019), I didn’t feel like I had finished a movie. Instead, I felt like the movie had finished something inside me — maybe my assumptions about success, morality, and control over life. This is not simply a story about rich and poor. It is a layered meditation on human survival.

From the first frame to the last, the storytelling is precise and almost surgical. Nothing is wasted. Every object, every staircase, every smell, every drop of rain means something. The drama is impeccable, supported by deeply human performances from the cast — Song Kang-ho as Kim Ki-taek (father), Jang Hye-jin as Chung-sook (mother), Choi Woo-shik as Ki-woo (son), Park So-dam as Ki-jung (daughter), Lee Sun-kyun and Cho Yeo-jeong as the wealthy Park couple, and Lee Jung-eun as the former housekeeper Moon-gwang. Even the minor characters feel necessary, like pieces of a chessboard.

It is rare for a film to feel so perfectly assembled.

The Opening: Poverty Without Drama

What struck me first was the simplicity of the beginning.

No background music forcing emotion. No exaggerated suffering. Just a semi-basement house, low windows, drunk men peeing outside, and a family folding pizza boxes for money. This is poverty presented without cinematic decoration.

One small but important detail is Chung-sook’s past. She was a hammer throw champion. She even has a certificate. That small prop says so much. Talent existed. Hard work existed. But opportunity didn’t. The system did not reward her. Society quietly discarded her.

This tells us something powerful: poverty is not always the result of laziness. Sometimes it is simply structural neglect.

The Kim family is not incompetent. They are smart, adaptive, and skilled. Yet they are stuck.

And this is where Parasite begins asking its first question: If talent is not enough, what really determines success?

The Plan: Human Ego and the Illusion of Control

The Kims create a meticulous plan to infiltrate the Park family’s house. One by one, they replace the driver, the housekeeper, the tutor, and the art therapist. It is clever, almost funny. For a while, we feel proud of them. It feels like a heist film.

But then comes Ki-taek’s famous line: “You know what kind of plan never fails? No plan at all.”

This line stayed with me long after the film ended. It strangely reminded me of a verse from the Bhagavad Gita:

Karmanyevadhikaraste ma phaleshukadachana

“You have the right to action, but not to the fruits of the action.”

The Kim family believes they are the authors of their destiny. They think if they plan perfectly, life will obey. But life doesn’t obey.

The hidden basement exists. The old housekeeper returns.

The rain comes. The “smell” exposes them.

All these uncontrollable forces destroy their perfect strategy. This is where the tragedy lies.

The Gita teaches detachment from results. But modern life forces us to chase results. The Kims’ suffering comes from this clash. They plan because they must survive. Yet the world reminds them they are not fully in control.

Ki-taek’s “no plan” philosophy is not laziness. It is exhaustion. It is the broken wisdom of a man who has tried too many times and failed. It is the philosophy of someone society has defeated.

Architecture as Class Division

One of the most genius aspects of Parasite is how class is shown visually, not through speeches. The Park house is modern, clean, open, and elevated. Sunlight enters freely. Everything is horizontal and spacious. The Kim house is underground, cramped, and damp. Even the toilet is raised awkwardly. They literally live below street level.

The film constantly uses stairs.

Upstairs → wealth

Downstairs → poverty

Whenever the Kims go to work, they climb up. Whenever they return home, they descend.

This is not accidental. Bong Joon-ho turns architecture into social commentary. Class is not just money. It is geography. Where you live physically becomes where you stand socially.

The Rain: Beauty for Some, Disaster for Others

One of the most heartbreaking sequences is the rainstorm.

For the Park family, rain is romantic. It clears the air. It creates a beautiful camping mood for their son. They wake up happy and refreshed.

For the Kim family, that same rain floods their entire home. Sewage water overflows. Their belongings float away. Everything they own is destroyed.

Same rain. Two different realities. This scene perfectly captures inequality. Nature itself becomes political. The rich experience inconvenience. The poor experience catastrophe.

It quietly says: comfort depends on distance from suffering. If you are rich enough, disasters look aesthetic.

The Smell: The Invisible Border

Perhaps the most painful motif in the film is “the smell.”

The Parks repeatedly mention the smell of the Kims — a subway smell, a basement smell.

This is devastating because smell is something you cannot hide easily. Clothes can change. Language can change. But smell? It betrays you.

It becomes a biological marker of class. No matter how well the Kims perform, they can never truly belong. There is always an invisible border. And that border finally breaks Ki-taek’s dignity during the climax.

When Mr. Park holds his nose in disgust while Ki-taek is grieving his injured daughter, something snaps inside him. That murder is not planned. It is not strategic. It is pure humiliation exploding. In that moment, Ki-taek is not killing a man.

He is killing years of silent disrespect.

Who Is the Parasite?

The title itself is genius.

At first, we think the Kims are parasites — living off the rich family. But slowly the question flips.

The Parks cannot cook, clean, drive, or manage their lives without workers. They depend entirely on labor from the lower class.

So who is the parasite? Maybe both. Maybe society itself is parasitic.

The rich feed on cheap labor. The poor feed on opportunities created by the rich. Neither exists independently.

Even Moon-gwang and her husband parasitize the Parks secretly in the basement. It is layers of dependence.

A cycle with no clear villain. That’s what makes the film uncomfortable.

It refuses to give us a hero.

The Ending: Hope or Illusion?

The final scene shows Ki-woo dreaming of earning money and buying the house to free his father.

At first, it feels hopeful. But then reality returns. We see him still in the same semi-basement. The plan is just a dream.

And we understand something tragic: For people trapped in structural poverty, even hope becomes fantasy.

The system doesn’t change just because you wish harder. This ending doesn’t offer victory.

Everyone loses.

The sister dies.

The father hides underground.

The son lives with guilt.

The Parks lose their comfort.

No one wins. Which makes the film feel painfully real.

Conclusion: What Parasite Left Me Thinking

After finishing Parasite, I didn’t feel entertained. I felt exposed.

It forced me to confront uncomfortable questions: Is success really merit-based? Are we truly in control of our lives? Is morality even possible when survival is at stake?

Maybe the film isn’t trying to answer these. Maybe it just wants us to observe.

Because in the end, we are all connected in this strange ecosystem of need, exploitation, and dependence.

Maybe everyone is a parasite to someone else. And maybe the only thing we truly control — like the Gita suggests — is our action, not the result. The rest is fate, society, and circumstance.

Parasite is not just cinema.

It is a mirror.

And sometimes, mirrors are uncomfortable to look at.

Bio:

Praveen Kumar is a movie lover and one day aspires to become a Movie Director. He’s also founder of HuntingForKicks.com.